Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Journalist Extraordinaire (1862-1931)

March 3, 2023

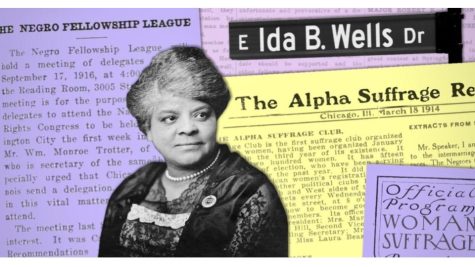

Image from Wbez Chicago

Image from Wbez Chicago

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was an American investigative journalist, civic leader, civil rights activist, and mother of intersectionality during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Wells-Barnett battled racism, misogyny, and violence during her lifetime by using her skilled ability as a writer. As a journalist, she wrote about issues of race and politics in the South and was a vocal female activist in the early women’s suffrage movement. Through her work, she earned the title “Princess of the Press.”

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862. Although she was born into slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation eventually led to her freedom. During that period of freedom, the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878 took the lives of her parents and younger brother. Afterward, she relocated to Memphis, where she established the Free Speech and Headlight Newspaper to cover discrimination and segregation firsthand.

Wells-Barnett grew up during the time of American Reconstruction following the Civil War, when white people were hostile to any Black person who wanted an education, property, or any means of social mobility. Tensions were high as white mobs began to terrorize the South, driving black citizens out of town so they would not be able to assume positions of authority. Worst of all, lynchings were growing even more common: “Lynchings were violent public acts that white people used to terrorize and control Black people” (NAACP). A single rumor would incite a white mob to attack a Black citizen, who would then be shot, dragged, hanged, and beaten. According to a recent estimate by Smithsonian: “The number of victims of racial terror killings between 1865 and 1950 to almost 6500.” In 1890 Wells-Barnett led an anti-lynching crusade and documented lynchings in the United States through her pamphlet, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Wells-Barnett was one of the first people to stand up against lynchings and call them what they were: a scare tactic. She was not averse to making enemies and was unafraid to speak out in favor of encouraging her race to preserve their newly won rights. This led to a white mob destroying her newspaper office, forcing her to move to Chicago.

At incredible risk to herself, she started meticulously documenting lynchings in detail, traveling to investigate them, interviewing eyewitnesses, and establishing that the lynchings had been carried out falsely. Later her work got the public’s attention and an anti-lynching bill was finally introduced in 1918.

Wells-Barnett was the intersectional embodiment of history that brings race and gender together. Ida B. Wells-Barnett was one of the early figures that were ignored by the women’s suffrage movement because of how she opposed racism being normalized in the early feminist waves. She would blatantly call out white feminists for condoning racism and lynchings as justifications for women’s rights. Wells-Barnett was ahead of her time and examined intersectionality’s nature before the term was even coined. According to the National Women’s History Museum History, “Wells-Barnett traveled internationally, shedding light on lynching to foreign audiences. Abroad, she openly confronted white women in the suffrage movement who ignored lynchings.” Wells-Barnett founded the Alpha Suffrage Club and the National Association of Colored Women Club to fight racism and sexism, to ensure that her voice was heard and that her vote was counted because “without sacredness for the ballot, there can be no sacredness for human life itself,” she said. Despite being frequently mocked and excluded by white women’s suffrage organizations in the United States because of her stance, she persisted.