A Woman’s Memoir: An Exploration of the Complex Body

March 18, 2022

TW: sexual assault

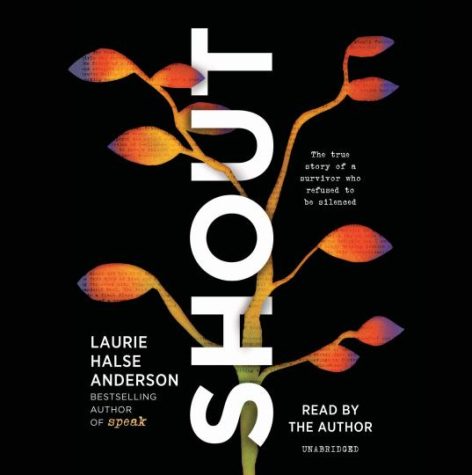

Laurie Halse Anderson explores the complexities and intricacies of the female gender in her award-winning memoir, Shout.

Laurie Halse Anderson explores the complexities and intricacies of the female gender in her award-winning memoir, Shout.

Written in verse, Anderson portrays her point of view emphatically on each page. She urges that it shall be discussed the manner in which women are objectified for the amusement of men and the sexism and cruelty surrounding this societal norm. It shall be asked why the man feels a woman’s skin is his. Consent, she explains, is the basis for peace among humans—a life lesson for all. The concept promotes a feeling of safety, a sense of security.

At thirteen years old, Anderson was raped. A purposeful selection of words, the rapist is referred to as “IT” throughout the book, as to demean his true identity and highlight the significance of the true event–-the assault. Perchance, this was strategic as to stimulate conversation of such matters in the media. Noticeably, when terroristic acts occur within our nation, the media focuses on the convict rather than the victim. This can be seen in issues regarding mass shootings and prejudiced offenses as well as matters of sexual assault. To recognize the magnitude of the ideals aside from the assailant’s identity, Anderson creates a nickname of sorts for him–a truly admirable act.

Intertwined with lines of poetry, didactic stories are woven through Anderson’s memoir. Each story chronicles a different contemporary issue in the author’s life. An empathetic figure in the lives of female, teenage readers, the author is truly brought to life through her detail. In one case, Anderson assesses the inner workings of the female body years after her assault, connecting with the sensitivity and emotions of her audience. A heroine to the woman and a menace to the misogynists, Anderson pushes the boundaries built by society regarding menstruation. She enhances the beauty of it, stripping away the plastered walls of disgust created by men centuries ago: “our bodies are muddy rivers, overflowing the banks to fertilize the fields” (224).

Anderson valiantly introduces the idea of normalizing conversations deemed inappropriate or uncomfortable. Menstruation is an idea she concentrates on, urging the regulation of knowledge of this bodily function. If deemed unsuitable for conversation, it should be asked how women are supposed to learn of their body’s neutrality.

Menstruation is an idea she concentrates on, urging the regulation of knowledge of this bodily function. If deemed unsuitable for conversation, it should be asked how women are supposed to learn of their body’s neutrality.

A love letter to women and an educational note for men, Shout was crafted from the hands of a survivor. Anderson urges her readers to sew the ripped stitch between genders in society. She encourages women to speak bravely and to speak the truth: “The false innocence you render for them by censoring truth protects only you” (193).